Manure Collection: Conversion from Flush to Scrape or Vacuum Systems

alternative practice names:

Tractor Scraper; Mechanical Barn Scraper; Chain Scraper; Vacuum Scraper; Robotic Scraper

Dairy operations generate manure and wastewater that can be handled as a solid, slurry, or liquid. In flush systems, large volumes of water are used to collect and transport manure, resulting in a liquid form. Liquid manure from flush systems often requires different handling and treatment processes compared to slurry. For instance, flush systems may incorporate sand settling lanes, rotary drum screens, and other separation technologies to manage the liquid manure effectively.

Handling dairy manure as a slurry instead of a liquid offers management and environmental benefits and enables the implementation of other conservation practices. Slurry manure is a more concentrated nutrient stream with a higher solids content.

Farms that currently use a flush system can fully or partially convert their manure collection system to a scrape- or vacuum-based system to take advantage of these conservation opportunities. Collection methods are summarized below:

Scraping systems: A blade or tire scraper on a tractor or skid steer is used to push manure and waste material to a collection point, such as a reception pit. The waste is then transferred to a storage area.

Vacuum systems: Using either self-propelled or tractor-pulled vacuum units, these systems suck the manure into a storage vessel for transfer.

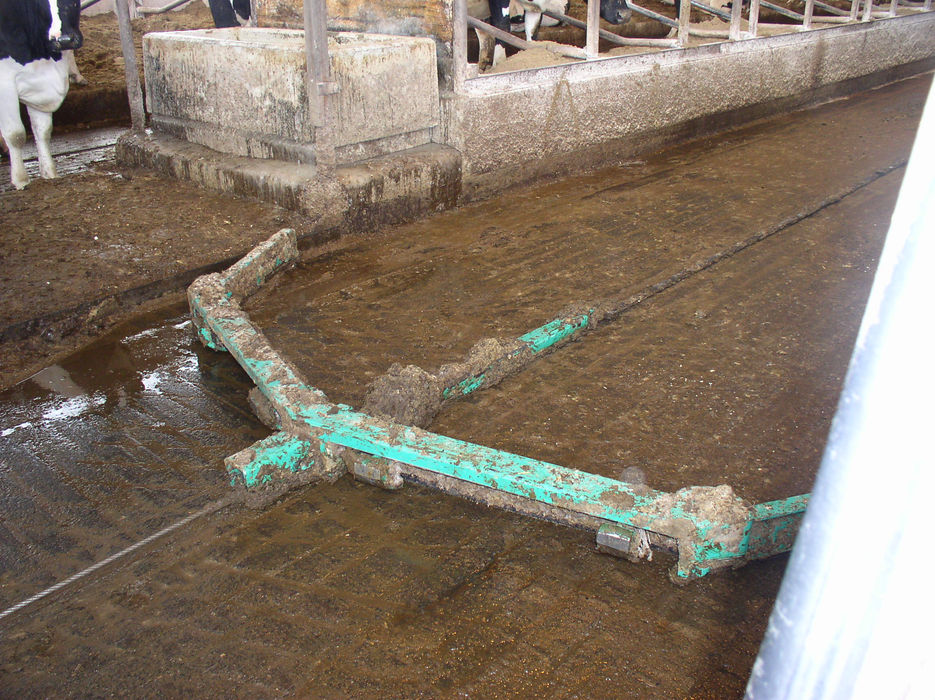

Automated scraping systems: These systems operate with limited oversight and perform scraping on a set schedule throughout the day. Automated systems include chain or cable scrapers and robotic scrapers.

Slatted floor systems: Slatted floors allow manure to fall through slats into a collection area below.

Once manure is collected as a slurry, it can be more easily dried and managed as a solid. Farms can also choose to partially convert from a flush system to a scrape or vacuum system. These farms might flush the manure a few times a week, diverting the liquid manure to an irrigation system. On other days, they can collect manure using a scrape or vacuum mechanism, allowing it to be dried and transported.

When used, in what regions in the U.S. is the practice found:

Northwest, West, Upper Midwest, Southwest, Southeast

FARM SIZE

When used, typically found on farms of the following sizes:

All Sizes

Practice Benefits

Reduced spreading costs: Much of the water in manure is lost via evaporation. The resulting product from this practice will be less expensive to transport and spread, and the nutrients will be more concentrated.

Compatibility with other technologies: Other manure management technologies may be more economical or only viable for farms where the manure is concentrated in a slurry.

We're always eager to update the website with the latest research, implementation insights, financial case studies, and emerging practices. Use the link above to share your insights.

Implementation Insights

Site-specific or Farm-specific requirements

Flush system: The practice is only applicable to farms that currently use a flush system to collect manure.

Manure storage set-up: When evaluating whether to use automated scrapers, vacuum trucks, or manual scraping, a dairy operation will need to consider its current manure storage set-up in relation to barn alleys.

Required Capital Expenditures (CapEx)

Collection equipment: Scraping can be done using a tractor and scraper, but opting for automated systems or vacuum trucks will involve higher initial capital expenses.

Concrete lanes and alleys: The cost of concrete lanes and alleys for manure removal will vary based on the current condition of the existing infrastructure. Some farms may need only minor modifications to improve access, while others may require new flooring or curbing to optimize manure collection.

Reinforced curbs: Reinforced curbs are designed to prevent manure spillage and help contain waste within designated areas, reducing the risk of migration to unwanted zones.

Manure transfer systems: The method used to transfer manure can influence infrastructure requirements, such as the need for gutters, channels, reception pits, or pushoff ramps. Given the change in manure solids content, different pumps may also be necessary to move manure from the collection pit to storage or treatment systems.

Required Operational Expenditures (OpEx)

Routine collection equipment maintenance: Regular maintenance of manure scraping equipment is crucial to ensure the reliability and proper functioning of the manure management system. Well-maintained equipment helps avoid unexpected breakdowns and keeps the system operating smoothly.

Labor considerations: Labor is an important factor in manure management. Operating equipment like tractors, vacuums, or bobcats for scraping may require dedicated personnel, while automated scraping systems, though more hands-off, still require regular monitoring and maintenance to ensure consistent performance.

Concrete repair and replacement: Periodic repairs to damaged concrete are important to prevent manure spillage and to avoid fragments from entering the waste management system, which could potentially damage equipment. Maintaining smooth, intact concrete surfaces helps ensure the efficiency and longevity of the overall system.

Implementation Considerations

Manure storage lagoons: For farms using lagoon systems designed for specific organic loading rates, it is important to consider how changes in manure collection methods may affect lagoon performance. Consulting with an engineer can help assess whether the system can handle alterations without compromising treatment efficiency.

Equipment durability: When choosing equipment for manure handling, durability in corrosive environments is a key consideration. Systems that involve sand can cause abrasion, so regular maintenance is needed to prevent equipment failure and ensure consistent operation. Overloading equipment beyond its design capacity can damage concrete surfaces, potentially leading to costly repairs.

Water management: Managing water from precipitation is crucial in maintaining manure volumes. Rain and snow that accumulate on concrete lanes and alleys can increase the total volume of waste, so separating this water from manure storage is important. Roofing over scraped areas and directing runoff away from the manure system can help keep clean water clean, reducing the amount that enters the storage system.

Scraping frequency: Scraping frequency is a significant factor in managing manure build-up. How often scraping occurs depends on operational preferences and time availability. Ensuring regular scraping helps prevent excess manure accumulation in alleyways.

Cow movement: Scraping activities can interfere with cow movement, so timing is important. Scraping while cows are in the milking parlor or confined to other areas can minimize disruption. Automatic scrapers, which operate continuously, are often compatible with cows being present in the pen.

Financial Considerations and Revenue Streams

FEDERAL COST-SHARE PROGRAM

Funding is available for this practice through USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

Related EQIP Practice Standard: Waste Transfer (634).

Notes:

Check with the local NRCS office on payment rates and practice requirements relevant to your location.

To quality for EQIP funds, the dairy is required to obtain a Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan (CNMP) to guide practice implementation.

Environmental Impacts

MAY REDUCE FARM GREENHOUSE GAS FOOTPRINT

Converting a flush system to a scrape or vacuum barn can alter a farm's environmental footprint by changing how manure is managed. Switching to a scrape manure collection system may lead to the formation of a crust on the manure lagoon, which can help reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during manure storage.¹ However, some studies have reported higher ammonia and methane emissions in barns using scrape systems compared to flush systems.² If a farm transitions from a flush system to a scrape or vacuum system and further manages manure as a solid, such as through solar drying, methane emissions can be significantly reduced (see Composting: Static Stacking and Windrows).³

────────────────

¹ A natural manure crust can reduce manure-associated methane emissions by 21% (Petersen et al., 2005).

² Ross et al. (2021) concluded that scraping manure in free-stall lanes may increase emissions of NH₃ and methane compared to collecting manure via a flush system within the barn; the study did evaluate the impact of the different manure collection practices on manure storage emissions.

³ While the full extent of this impact is not completely understood, models (FARM ES and California Air Resource Board Model) indicate that transitioning from liquid to slurry management and managing the manure as a solid could reduce up to 70% in emissions associated with manure storage.

REFerences

Contents

We're always eager to update the website with the latest research, implementation insights, financial case studies, and emerging practices. Use the link above to share your insights.

Alignment with FARM Program

FARM Environmental Stewardship (ES) V2-V3 Alignment

FARM ES Version 3 offers various manure handling options including manual scraper, alley scraper and flush.

Dairy operations generate manure and wastewater that can be handled as a solid, slurry, or liquid. In flush systems, large volumes of water are used to collect and transport manure, resulting in a liquid form. Liquid manure from flush systems often requires different handling and treatment processes compared to slurry. For instance, flush systems may incorporate sand settling lanes, rotary drum screens, and other separation technologies to manage the liquid manure effectively.

Handling dairy manure as a slurry instead of a liquid offers management and environmental benefits and enables the implementation of other conservation practices. Slurry manure is a more concentrated nutrient stream with a higher solids content.

Farms that currently use a flush system can fully or partially convert their manure collection system to a scrape- or vacuum-based system to take advantage of these conservation opportunities. Collection methods are summarized below:

Scraping systems: A blade or tire scraper on a tractor or skid steer is used to push manure and waste material to a collection point, such as a reception pit. The waste is then transferred to a storage area.

Vacuum systems: Using either self-propelled or tractor-pulled vacuum units, these systems suck the manure into a storage vessel for transfer.

Automated scraping systems: These systems operate with limited oversight and perform scraping on a set schedule throughout the day. Automated systems include chain or cable scrapers and robotic scrapers.

Slatted floor systems: Slatted floors allow manure to fall through slats into a collection area below.

Once manure is collected as a slurry, it can be more easily dried and managed as a solid. Farms can also choose to partially convert from a flush system to a scrape or vacuum system. These farms might flush the manure a few times a week, diverting the liquid manure to an irrigation system. On other days, they can collect manure using a scrape or vacuum mechanism, allowing it to be dried and transported.

Practices and technologies

Manure Collection: Conversion from Flush to Scrape or Vacuum Systems

alternative practice name:

Tractor Scraper; Mechanical Barn Scraper; Chain Scraper; Vacuum Scraper; Robotic Scraper

REGIONALITY

When used, in what regions in the U.S. is the practice found:

Northwest, West, Upper Midwest, Southwest, Southeast

COMPARABLE FARM SIZE

When used, typically found on farms of the following sizes:

0 - 100 cows, 100 - 500 cows, 500 - 2500 cows, 2500 - 5000 cows, Over 5000 cows

Practice Benefits

Reduced spreading costs: Much of the water in manure is lost via evaporation. The resulting product from this practice will be less expensive to transport and spread, and the nutrients will be more concentrated.

Compatibility with other technologies: Other manure management technologies may be more economical or only viable for farms where the manure is concentrated in a slurry.

Implementation Insights

Site-specific or Farm-specific requirements

Flush system: The practice is only applicable to farms that currently use a flush system to collect manure.

Manure storage set-up: When evaluating whether to use automated scrapers, vacuum trucks, or manual scraping, a dairy operation will need to consider its current manure storage set-up in relation to barn alleys.

Required Capital Expenditures (CapEx)

Collection equipment: Scraping can be done using a tractor and scraper, but opting for automated systems or vacuum trucks will involve higher initial capital expenses.

Concrete lanes and alleys: The cost of concrete lanes and alleys for manure removal will vary based on the current condition of the existing infrastructure. Some farms may need only minor modifications to improve access, while others may require new flooring or curbing to optimize manure collection.

Reinforced curbs: Reinforced curbs are designed to prevent manure spillage and help contain waste within designated areas, reducing the risk of migration to unwanted zones.

Manure transfer systems: The method used to transfer manure can influence infrastructure requirements, such as the need for gutters, channels, reception pits, or pushoff ramps. Given the change in manure solids content, different pumps may also be necessary to move manure from the collection pit to storage or treatment systems.

Required Operational Expenditures (OpEx)

Routine collection equipment maintenance: Regular maintenance of manure scraping equipment is crucial to ensure the reliability and proper functioning of the manure management system. Well-maintained equipment helps avoid unexpected breakdowns and keeps the system operating smoothly.

Labor considerations: Labor is an important factor in manure management. Operating equipment like tractors, vacuums, or bobcats for scraping may require dedicated personnel, while automated scraping systems, though more hands-off, still require regular monitoring and maintenance to ensure consistent performance.

Concrete repair and replacement: Periodic repairs to damaged concrete are important to prevent manure spillage and to avoid fragments from entering the waste management system, which could potentially damage equipment. Maintaining smooth, intact concrete surfaces helps ensure the efficiency and longevity of the overall system.

Implementation Considerations

Manure storage lagoons: For farms using lagoon systems designed for specific organic loading rates, it is important to consider how changes in manure collection methods may affect lagoon performance. Consulting with an engineer can help assess whether the system can handle alterations without compromising treatment efficiency.

Equipment durability: When choosing equipment for manure handling, durability in corrosive environments is a key consideration. Systems that involve sand can cause abrasion, so regular maintenance is needed to prevent equipment failure and ensure consistent operation. Overloading equipment beyond its design capacity can damage concrete surfaces, potentially leading to costly repairs.

Water management: Managing water from precipitation is crucial in maintaining manure volumes. Rain and snow that accumulate on concrete lanes and alleys can increase the total volume of waste, so separating this water from manure storage is important. Roofing over scraped areas and directing runoff away from the manure system can help keep clean water clean, reducing the amount that enters the storage system.

Scraping frequency: Scraping frequency is a significant factor in managing manure build-up. How often scraping occurs depends on operational preferences and time availability. Ensuring regular scraping helps prevent excess manure accumulation in alleyways.

Cow movement: Scraping activities can interfere with cow movement, so timing is important. Scraping while cows are in the milking parlor or confined to other areas can minimize disruption. Automatic scrapers, which operate continuously, are often compatible with cows being present in the pen.

Financial Considerations and Revenue Streams

FEDERAL COST-SHARE PROGRAM

Funding is available for this practice through USDA's Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) Environmental Quality Incentives Program (EQIP).

Related EQIP Practice Standard: Waste Transfer (634).

Notes:

Check with the local NRCS office on payment rates and practice requirements relevant to your location.

To quality for EQIP funds, the dairy is required to obtain a Comprehensive Nutrient Management Plan (CNMP) to guide practice implementation.

Research

REFerences

MAY REDUCE FARM GREENHOUSE GAS FOOTPRINT

Converting a flush system to a scrape or vacuum barn can alter a farm's environmental footprint by changing how manure is managed. Switching to a scrape manure collection system may lead to the formation of a crust on the manure lagoon, which can help reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions during manure storage.¹ However, some studies have reported higher ammonia and methane emissions in barns using scrape systems compared to flush systems.² If a farm transitions from a flush system to a scrape or vacuum system and further manages manure as a solid, such as through solar drying, methane emissions can be significantly reduced (see Composting: Static Stacking and Windrows).³

────────────────

¹ A natural manure crust can reduce manure-associated methane emissions by 21% (Petersen et al., 2005).

² Ross et al. (2021) concluded that scraping manure in free-stall lanes may increase emissions of NH₃ and methane compared to collecting manure via a flush system within the barn; the study did evaluate the impact of the different manure collection practices on manure storage emissions.

³ While the full extent of this impact is not completely understood, models (FARM ES and California Air Resource Board Model) indicate that transitioning from liquid to slurry management and managing the manure as a solid could reduce up to 70% in emissions associated with manure storage.

Alignment with FARM Program

FARM Environmental Stewardship (ES) V2-V3 Alignment

FARM ES Version 3 offers various manure handling options including manual scraper, alley scraper and flush.